When photographer John Wreford wrote for Roads & Kingdoms in March about going on daily errands in Damascus, his home for the previous decade—and the Assad regime stronghold—his bio included this: “He is not planning to leave Syria anytime soon.”

It was true in March. But war has a way of making a mockery of plans, and when I called John this weekend to talk about his new photos from the Atmeh refugee camp in northern Syria, he was not in Damascus anymore. Rather, he has joined, in his own way, the great flood of refugees throughout the region, having left behind his home and photo gallery in Damascus and moved to Istanbul. He was kind enough to spend an hour with us talking about refugees, international apathy, and the long tail of war.

Roads & Kingdoms: Thanks for taking the time to talk.

John Wreford: No problem. Just bear with me. My Mac died and I have a new computer. I don’t really know what I’m doing with it.

R&K: When did you leave Damascus? Why?

JW: It started just after you published my account. Famous last words: “He is not planning to leave”. And I wasn’t. But I had trouble.

In Syria, being “on the computer” is a euphemism for being wanted by the secret police.

R&K: What kind of trouble?

JW: [It started when] I was about to leave for a short trip for Cairo. I have residency in Syria, and to leave you have to get an exit visa. When I went to the immigration office to do it, I discovered my name was on the computer. In Syria, that’s a euphemism for being wanted by the secret police. I spent the next three months trying to leave.

Eventually, I got permission. It’s ridiculous, these lists. They didn’t tell me what it was. One suspects that they were worried I was working as an undercover journalist. They gave me permission to leave, and according to the stamp in my passport, it allows me to go back. But there’s a big risk. You need little excuse these days to lock someone up. The handful of foreigners still left in Damascus are all having trouble.

R&K: Was it a proper move or did you have to just leave with a few suitcases?

JW: Pretty much the latter. The guy at the immigration office was a little bit soft, and we were paying him for his assistance, he said “you’re supposed to go to the Mukhabarat (the secret service), but my advice is to not go.”

So I went back home and just packed everything. Usually they just detain you at the immigration office, and then you just have 48 hours to leave the country. I had longer, but I still had to leave everything.

I’ve got somebody living in my house, people I know who are refugees from a different part of the city. I feel very much like a refugee.

R&K: What do you mean?

JW: That’s one of the things about the refugee crisis. The camps in Jordan and Turkey, they’re the worst of it, but it’s much wider than that. There are so many reasonably wealthy, middle class types who are all refugees. It’s very difficult for them to find visas. Very difficult to find work, because of the usual scenarios for foreigners. They are using up all their savings. They can’t really sell property or cars in Syria now. People are not used to being in the position of not being able to manage financially.

R&K: Do you still own your home in Damascus?

JW: I do.

R&K: And Istanbul is now full of your Syrian friends?

JW: Yes. It’s actually quite amusing. I lived in the old city of Damascus, and I had a small photo gallery, with a friend, in the touristy area. I knew everyone. As the war went on, a lot of them left, and it was all new faces in my neighborhood. But a lot of the people working in the tourist industry, selling carpets and so on, they’ve all come here to Istanbul. When I arrived here, it was just like walking around old Damascus, saying hi to all the old familiar faces.

R&K: Why are so many in Istanbul in particular?

JW: People from Aleppo, they always have dealings with Turkey. And the tourist industry in Turkey is very similar to that in Syria. The things they sell are similar. Plus, Turkey over the last few years had had a large influx of Arab tourists, so it’s actually beneficial to have people who speak Arabic in the shops. You hear them calling out in Arabic through the Bazaar now. Quite amusing.

R&K: You miss Damascus?

JW: It wasn’t a love affair, it was more of a fascination. I have made my home there, but even buying the house, that wasn’t putting down roots, it was a last chance property investment. There was such a boom in the in the old city (before the revolution), I thought it couldn’t possibly fail. [laughs]

Coming to terms with not being able to go back is difficult. Very difficult.

R&K: A couple weeks after moving to Turkey, you went to northern Syria to photograph the Atmeh refugee camp. Why?

JW: For the last two years I lived in Syria, I’ve not been able to photograph anything, and this of course is frustrating. As a photographer, as a journalist, Syria is something personal. If my situation had been different, I would’ve done it differently. I would’ve come in through the north and photographed the Free Syrian Army.

But I was already in Damascus, and I felt it important to stay, to understand what was going on, to be part of it. The media has often gotten it very wrong, or just not reported things. There’s a lack of attention paid to ordinary Syrian people living their lives.

As a photographer, the most natural thing would be to photograph the most dramatic fighting. But living there, I feel like it’s a small part of the story. It’s important and integral, but it’s not the whole story.

R&K: How did you get to Atmeh camp?

JW: From Istanbul flying to Antakya, and then there’s a small town close to the border called Reyhanli. There are lots of Syrian activists and journalists in both places; this is the base that they’re using.

I think it’s important to point out that the help that people are getting in Atmeh comes from Syrian activists. They are people who were active in the beginning of the revolution, but who have elected not to go the path of violence, and are instead trying to build up civil society. In Atmeh camp, they’re building a bakery, a hospital. And they’re taking incredible risks.

I knew a guy who delivered a truckload of flour deep into Syria—8-10 hours each way. It’s an incredible risk, just to make sure flour gets to the right people.

[narrowImg]

R&K: What was it like to cross the border there?

JW: It’s kind of strange. You stop off before you get to the border, at a Turkish police post, or something like this. It’s not official, but they facilitate the taking of names. I was with the [US-based NGO] Maram Foundation, and they are well-known there. So there’s a little bit of paperwork, then you drive to the border, which is basically a farmgate manned by a couple Turkish police.

It’s almost like a south of France camping experience… at first.

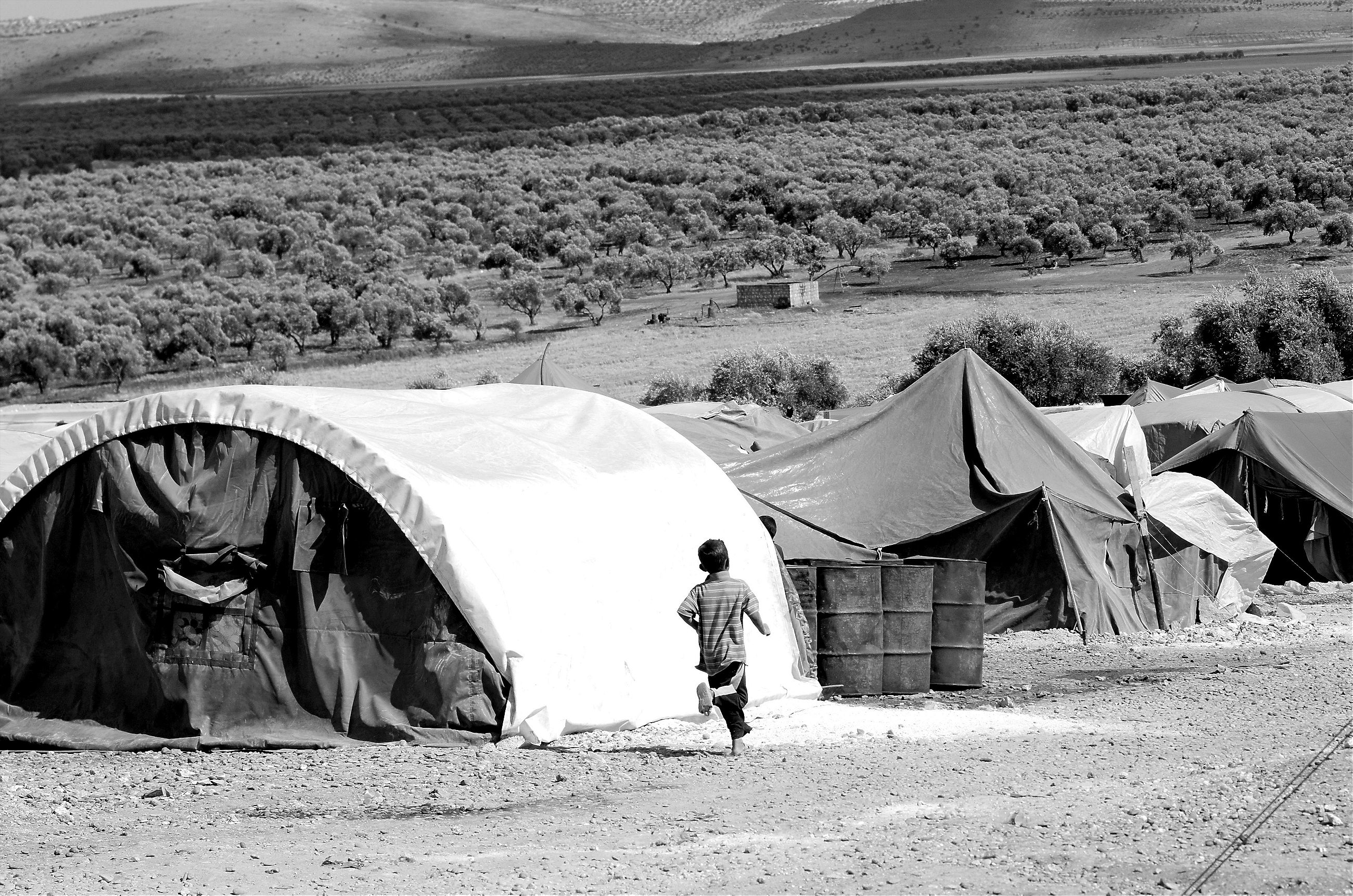

The separation between Turkey and Syria is just rolls and rolls of razor-wire. As you enter the camp, you just go up a slight incline and then you get more of a view of the surrounding area. In normal circumstances, it would be one of the most beautiful parts of Syria: green rolling hills, olive groves. Syrians were always frustrated that the rest of the world doesn’t realize how green Syria is—and this is that part of the country. It’s almost like a south of France camping experience… at first. But then the camp just goes on and on and on.

We were wearing t-shirts of the foundation, and they discolored within a couple of hours. It’s very rich red earth there, and it’s everywhere. Everything was absolutely covered in this thick red dust.

This is summer. And when it rains—this part of Syria gets some proper harsh winter weather—it will be an absolute river of mud. It will be a nightmare, really.

R&K: Were you bringing supplies with you?

JW: We were there in support of another NGO called Karam , set up out of America before the revolution but now working specifically on Syrian aid. They wanted to do something for the children of the camp, so we visited with a Syrian artist, a writer, a dentist, another photographer. They had various events planned, firstly to entertain the children, to train the locals to continue this. They built a playground and football field. The photographer was teaching people how to coach football. The dentist taught dental hygiene. There were some art classes.

These children have had a year and a half of absolute hell. They’ve been described as the lost generation, and it’s true.

R&K: How many children are there in Atmeh?

JW: The numbers are a bit difficult to pin down. There is some coming and going. People would rather go back to areas that are considered liberated than stay at the camp.

But 20,000 to 25,000 is the estimate, and around half are children.

This is my issue with the media. It always needs a new headline.

R&K: We’ve been reading a lot about the fall of Homs and the government’s new momentum. Are people worried they’ve lost?

JW: This is my issue with the media. It always needs a new headline. At the beginning of war, there was a lot of attention on refugees, and then it just stopped. It was the same at the beginning of the Iraq war: attention at first, but two years later nobody cared. But after two years of being a refugee, the story is considerably worse.

But of course the media needs to move on to something different. With Syria, you have the taking of a town, the back and forth of the opposition and the regime, the changing face of the opposition and so on. For the Syrians, though, it doesn’t really affect them.

Nobody has in Syria has any form of security. Whoever’s in charge, whatever their feelings are. The recent New York Times article says that government is winning. There’s a little bit of truth to that, but in the same article, it says they’ve lost 60% of the country. What kind of winning is that?

The visiting journalists, particularly on the regime side, don’t get the full story. The New York Times wrote that mortars, which had been “peppering” Damascus, have stopped. They haven’t. That’s not true. Mortars have been falling into Damascus intermittently now for a year, and they’re still falling.

The regime has the details of what’s going on in Syria, nobody else does. Everyone else has to read between the lines.

But you also have to remember that Syrians are not reading the NYT. Generally speaking, people know it’s a mess, and its not getting better soon.

R&K: So you don’t think the government is on the brink of victory?

JW: I think it’s a stalemate. There might have been a time when people thought that the FSA with their momentum could go straight to Damascus. But that will only happen with the right kind of foreign support. And really, it has to be substantial support—the government has tactical missiles and air superiority. So when the British government announced they were giving the rebels communications equipment and chemical weapons protection, well…

R&K: The town of Atmeh had been bombed by the regime. Was there a worry of an airstrike on the refugee camp?

JW: The day that we arrived at the camp, there was a warplane bombing literally across the valley. As we arrived, people had scattered and run to hide. We had no idea what was going on. People knew exactly where they were going to hide and what they were going to do. I didn’t see the plane, but I did see the smoke coming from towns and villages across the valley.

That being said, you get a false sense of security when things are quiet. I felt this in Damascus. It’s quiet, and then you think that it will stay that way.

People outside don’t want to help, because they think it’s just terrorists fighting a dictator.

R&K: Did spending time in the liberated area of Syria change your mind?

JW: My understanding about Syria and its people is not an academic one; it’s from living in the country. As a photographer, I worked with a lot of NGOs and traveled to every corner of the country, in fairly remote places like Hasakah and Qamishli. Of course, I felt fairly comfortable with my own opinions, but you start to doubt things, reading the media every day in Damascus.

I do think this: the religious [extremism] of the rebels that you read about in Damascus is overshadowing the reality of what’s happening in Syria. It’s clearly happening, but it’s people from outside of Syria. Syria has always been a moderate relaxed country when it comes to religion. Places like Dubai are far more restrictive.

Right from the beginning there were so many images of rebels with beards and Kalashnikovs and chanting Allahu Akbar, as if this was all there is in Syria. And then people outside don’t want to help in any way, because they think it’s just terrorists fighting a dictator. But the majority of people, they’re more culturally Muslim than religious. In no way do they aspire to a Saudi or Salafi thing.

That said, people opposed to the regime will pretty much take the support of anyone who is offering. The Israelis bombed a military camp, and there wasn’t a lot of condemnation from people inside Syria.

R&K: Is the Atmeh camp still growing?

JW: If the regime starts to move toward retaking towns in the north, you’ll see a lot more people come in. Predominately right now they’re from the nearer towns and villages. For the last two years, people have been moving all around the country to find safety.

Even in Damascus, people have been moving from neighborhood to neighborhood, trying to figure out where they would be safe.

R&K: How is the situation with disease in the camp?

JW: I don’t think there’ve been any serious outbreaks of disease. But there have been elsewhere. You do feel one case and it would spread very quickly. Every thing has to be paid for in the water. Water is bought and trucked in. There’s no electricity. Day to day, everything is a struggle. People like Maram are getting money through donations and various sources, but clearly with a population with that size, I think malnutrition is a big worry.

The people of Syria feel abandoned.

R&K: Why is the UN not there?

JW: They need permission from the regime, officially. And since they won’t get permission, they won’t go in. They do have some kind of emergency arm of the UN that could potentially overcome these problems. But as far as the UN is concerned, it’s out of their control.

In my mind, looking after the refugees shouldn’t be a logistical difficulty. We just walked through a farm gate and did what we could do.

There are organizations to help, like the Karam foundation. But the UN has vast experience and infrastructure for these things. It’s just that the political will to solve the situation is just not there.

I don’t want to get into the debate about arming the rebels, but there has to be the political will to solve the problem. And it’s not there. The people of Syria feel abandoned.

R&K: Will you continue to work in the camps?

JW: My interest is with Syria. And from living the last two years and being sort of frustrated for lots of different reason, I just feel it’s important to continue to try to raise awareness.

On a personal level, I need to earn a living, and I need to concentrate on that. For the last ten years I’ve been the guy in Damascus. It was a niche and quite comfortable. I need a new niche.

But I’m also still torn as to whether I’m going back to Damascus. Part of me is hesitant to do too much here.

I’m still not convinced I’m not going back.